At the outbreak of World War II, the Empire of Iran declared itself neutral. In 1941, after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, the allies needed to ship supplies and war matériel to the Soviets through Iran. This would have violated Iran’s neutrality so Britain and the Soviet Union simultaneously invaded Iran on August 26, 1941. The invasion was successful and the allies were able to ship over 5 million tons of supplies across the Iranian frontier into the Soviet Union.

At the outbreak of World War II, the Empire of Iran declared itself neutral. In 1941, after Hitler invaded the Soviet Union, the allies needed to ship supplies and war matériel to the Soviets through Iran. This would have violated Iran’s neutrality so Britain and the Soviet Union simultaneously invaded Iran on August 26, 1941. The invasion was successful and the allies were able to ship over 5 million tons of supplies across the Iranian frontier into the Soviet Union. On September 16, 1941 the pro-West Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi ascended to the Peacock Throne after his father abdicated. He ruled as the Shah (or Emperor) of Iran until he was deposed in the Islamic Revolution of 1979. In an attempt to build up American influence in Iran, the United States provided the Shah with a military assistance as well as assisting with the establishment of an internal security force under his direct command.

The Imperial Iranian Gendarmerie was the first modern highway patrol and rural police force in Iran. Established in 1910, the Gendarmerie went through several changes over the course of the Twentieth Century.

In December 1921, at the same time the New Jersey State Police was beginning its first patrol, the Gendarmerie was amalgamated into the Iranian Army. Four months later, the Iranian parliament established a new Gendarmerie. It was a relatively weak police force and was scattered throughout the Persian countryside. According to the Encyclopaedia Iranica, “...it’s main duty was to give warning of the existence of robbers and to identify the perpetrators of any robbery, generally leaving their pursuit and capture to the army...the broad responsibility for tribal pacification and rural control...remained with the army.”

After the Anglo-Soviet invasion of 1941, the Allies met with the Iranian government to discuss the country’s security and policing needs. In late 1942, the Shah’s government and the United States “...reached a series of agreements for the provision of American advisers” to assist with the military, the police and finances. General George Marshall, Army Chief of Staff, met with Colonel H. Norman Schwarzkopf and ordered him to Tehran as an advisor to the Imperial Iranian Gendarmerie.

Known as GENMISH, the mission to Iran was to “advise and assist the Persian ministry of the interior in the reorganization and training of the Gendarmerie...” As could be expected, GENMISH, and Colonel Schwarzkopf in particular, were the targets of both popular and organized nationalist opposition. Even the Shah was unhappy, being “...incensed at the very broad powers exercised by Schwarzkopf.”

A total of twenty-four American officers and enlisted men worked to reorganize, train, arm and command the 20,000-strong rural paramilitary police force. “By 1944-45, GENMISH had achieved considerable success with its reorganization, recruitment and training programs and had gone some way towards re-establishing the central government’s authority in the countryside. By December 1944 the US military attaché in Tehran believed that the army and Gendarmerie had improved to the point where Allied troop withdrawals would not jeopardize the security of the central government.” (Encyclopaedia Iranica)

It is interesting to note that, while Schwarzkopf was under the jurisdiction of the American Minister in Tehran and later the War Department, “...if the British...should employ the Gendarmerie to maintain security [in their region of Iran], then Colonel Schwarzkopf, in his capacity as an officer of the Gendarmerie, would come under British command.” This provision of the GENMISH mission never came into force.

Early on during his tour of duty, Schwarzkopf familiarized himself with the problems facing the Gendarmerie, visited the Gendarmerie posts throughout the countryside and reported his findings to the Iranian Minister of the Interior and eventually presented the Prime Minister a plan for the reorganization of the Gendarmerie.

By the end of summer 1944, Schwarzkopf established training schools “...for sergeants, motorcycle riders, and truck drivers, and had planned six others.” He also arranged for the United States to send a radio engineer to install a communications system. This was only a small fraction of his overall plan for the Gendarmerie, but he had learned that “...the work of his mission [was] beset with conditions of intrigue and inefficiency marked by a succession of eleven ministers of interior during the two years after his arrival.”(Motter, 1952).

The Iranians did accept nine demands Schwarzkopf put forth for the Gendarmerie, including remaining independent of the Army, a budget, pensions, the establishment of an elite corps, genuine government support of the GENMISH mission’s efforts, and the elimination of graft, red tape and reform delays. (Motter, 1952).

Although by the end of the war many of the reforms had not been implemented, the achievements of Schwarzkopf and the GENMISH mission were considerable. Most important was the improvement of the overall condition of the Gendarmerie and the creation of an esprit de corps among the ranks. Fighting illiteracy and opium addiction amongst its members, progress was finally able to be made. Under Colonel Schwarzkopf, the Gendarmerie rank and file “...moved steadily toward a better sense of discipline and respect.” (Motter, 1952).

Once again, H. Norman Schwarzkopf was able to beat the odds and transform an ineffective rural police force into an efficient, honest and respectful “Outfit.”

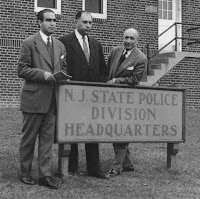

Photograph: Members of the Imperial Iranian Gendarmerie on a visit to New Jersey State Police Headquarters in West Trenton, 1955. (NJSP Museum Photo Collection)

Sources:

AllRefer Reference (http://reference.allrefer.com/country-guide-study/iran/iran19.htm)Encyclopaedia Iranica. (www.iranica.com/articles/v10f4/v10f448.html)

United States Army in World War II: The Middle East Theater. The Persian Corridor and Aid to Russia. By T.H. Vail Motter, Washington, D.C. 1952.